Q: Still about your music journey, how did you get to release the Risky Business EP? Was it because you had many songs or because you wanted to test the waters, given that you had been releasing only singles?

A: I wanted to challenge these uptown guys (Axon and his clique), but I also aimed to break into an entirely different market. After Risky Business EP, I started landing a lot of uptown shows, unlike the usual ones from my original Kawempe ghetto base, shows I had never accessed before the EP. The fan base grew. But beyond all that, I also released it because I had never put out a compiled body of work like an EP, and I felt it would be the perfect statement for a debut. I produced five of the songs on the EP, and when you think about it, that is risky business! Plus, everything in life involves risk, love, business, you name it, and this EP reflected all of that.

Q: The song Kampala did not have A Pass on it originally. How did you get him on the remix?

A: A pass has been a fan of mine since my first drop, Wansi, but of course, I was his fan long before that. Usually, whenever I drop new music, I make an effort to share it widely, with industry stakeholders, like Swangz Avenue, home and international artists and DJs, even someone like DJ Khaled.

I sent Kampala to A Pass, and his response was very positive; he even posted it on his Insta story for a while. He’s been supporting my music, liking my releases, dropping positive comments, and sharing on his socials. So with the Kampala remix, it was really about mutual respect, a bigger artist supporting a younger one he believes in. I think he saw a younger version of himself in me, hungry, talented, and talking about real things.

When I sent him the project details, he genuinely connected with the message. He said, “If I drop some lines on this, it’s going to get even bigger, you’re singing about something I really understand: the hustle of Kampala.” I sent the files through producer Nigel Beats, and within 24 hours, he’d already posted a preview of his verse on IG. That moment was crazy for me and my team.

When he finally sent the verse, it was madness, the energy, the love. The song took off, and to this day, Kampala is one of the biggest songs I have.

Q: Tell me how you pulled off Oscar Kampala’s 1000 Men Suits in the Kampala Remix Music Video?

A: That song was a blessing; everything just aligned. From A Pass to Oscar to the dancers, it all came together naturally. Oscar Kampala actually texted me first after hearing the song. We later linked up at his workplace, and he said he wanted to use the track for his 1000 Men in Oscar Kampala concept. We talked, teamed up, and eventually shot the video with his models. That alone saved me the cost of hiring people like that; it was all on him.

Even the dancers weren’t planned. They were rehearsing at the Independence Monument, where we were also planning to shoot. Their manager heard the song playing, liked it, and approached us asking if his dancers could be featured. The director gave them a scene.

The only real challenge we faced during the shoot was being denied access to Nakivubo Stadium.

Q: How did you push the Risky Business EP, considering the pressure and challenges that come with promoting an album or EP?

A: I honestly don’t look at it that way. Recording and releasing music is both my hobby and my job, so I don’t stress about pushing a particular song or project. For me, the momentum comes from consistently releasing new music. Everything else follows.

When I dropped the EP, I gave it space to grow. I played it for music patrons at the National Theatre, where there’s often a crowd, and I shared it with several other people. With time, the results showed, bookings increased, and a lot of other things shifted.

Q: Tell me about the other singles you’ve dropped after the first EP.

A: My career hasn’t been that long, so I can still remember my catalogue off-head. After Risky Business, I dropped Co-Driver, then Olaba Otya with Young Mulo.

Q: About the Young Mulo feature, I personally see you as an artist who belongs to the class of artistes that are to keep the industry active with constant releases, ensuring there’s no void when other ‘bigger’ artistes take their time between projects. Also, how is it that you worked with some of the older artistes like Young Mulo, who aren’t trendy now, when everyone else doesn’t seem to be doing that?

A: Most of that line of artists who have hit the roof, I am told, would love to work with me, and sometimes some openly confess they’d love for us to do something together: Zex Bilangilangi, Elijah Kitaka, etc. Young Mulo is one of them. He’s a fan of mine, and I’m a fan of his, too, so working on Olaba Otya wasn’t difficult.

The original verse of the song was in English, but Mulo suggested doing a Luganda chorus to make it more relatable. While freestyling the last verse, we came up with the line Olaba Otya, and he thought it was strong enough to be both the chorus and the title. That was his idea, and it worked.

Q: Now let’s talk about the Unscripted EP

A: Unscripted means unprepared for, and that’s exactly what this EP is. It’s a collection of 8 songs, mostly recorded last year, but in different, random places. Bad Like the 80s was recorded by J-Watts, Klin, and me. Jalia was recorded in Kisaasi in Kampala.

This EP isn’t limited to one style. It’s a diverse mix of sounds and ideas. Jalia, for example, represents my Masaka roots. I played it for my mama, and she said, “That sounds like Afrigo”.

Q: Let’s break down the EP song by song: What is Bad like the 80s about?

A: Bad Like the 80s is rooted in dancehall culture, which, like hip hop, relies heavily on self-hype. If you don’t talk about how ‘bad’ or tough you are, then it’s not really dancehall. That’s the energy the song brings out in me. It also represents us, the ‘90s kids who are now taking over the Ugandan music industry. It’s like Gen Z singing for themselves.

Q: Tell me about Omalayo

A: There’s a story behind the Winnie Nwagi line in the song. My hommies at Pyong Studio thought I had seen her before recording it, she’d actually been at the studio earlier. But I hadn’t seen her. The line just came naturally. If you’re talking about Ugandan women with voluptuous bodies, Winnie is the perfect symbol.

Q: About Ebyensi: The line ‘Gwewewala Emisana ekiro Yalikuyamba,’ what’s that about?

A: That is a flat line. The same person that you curse and hate might be the same person who might need to rescue you in a desperate situation. Life is an ecosystem where we need each other.

Q: Tell me about Company

A: It’s a love song about a girl, and the poetic lines are meant to express deep intimacy. It’s not dedicated to anyone specific. I don’t need to be inspired to sing about love, or anything I write about, because I’ve been through most of it. I’m not driven by a relationship, since I’m not in one. But I know what a relationship can do.

Q: Tell me about Njabala

A: I recorded Njabala in Najjera with producer Richies, who’s also from Kawempe. It was randomly added to the EP at the last minute; we both just wanted to have a song together.

Q: How about allergy?

Allergy is one of those beats that hit me instantly the first time I heard it. When it comes to songwriting, I don’t use pen and paper; I just flow with the beat. Klin had created the beat for some trio and asked me to write something for them. I recorded a draft, but when they heard it, they felt it wasn’t something they could perform. So Klin and I linked up again and decided to complete the song ourselves. The trio never mentioned the song again.

Q: Aside from music, what else do you do?

A: I only do music, nothing else. Music is the reason I live and breathe. I spend all my time in the studio recording and writing. I studied it, and I cannot disappoint myself by doing something else, like how a medical student cannot be a carpenter. The financial muscle comes from writing songs. I have dedicated all my life to music.

Q: What’s your stake on music as it is right now?

A: I think the industry is growing. Young artists are getting recognised, and they are breaking the gatekeepers’ control.

Q: Are your parents okay with you doing music?

A: My father passed away, and I started staying with my mum at 13, already a spoilt kid if you know what I mean. She could not do anything to change a lot about my lifestyle and choices. But she is proud of me and the music path I chose.

Q: What would be your message to a fan who listens to your music?

A: I would clap for them and congratulate them for landing on gold. To a typical fan, if you love a certain song, please share it with someone else, and support my craft.

Q: Do you hope to release some gospel music at some point, since honouring God is part of life’s journey?

A: Yes, I’ve written songs about God before. But there’s a time for everything. In every phase of life, there’s a moment to cry, to win, to reflect, and to give thanks. That time will come.

Q: In your view, what needs to change or improve for the music industry to grow stronger?

A: I personally think we should first educate ourselves and understand what we are doing. Besides that, we need unity and oneness in the industry.

Q: What’s your take on the fact that sometimes some people who participate in the production and distribution chain of music are left behind? Do you feel like an artist should grow with their people?

A: This is a human problem. But again, it’s important for everyone to know what they do for artists, especially since there’s no job security in many roles within the industry. You could get fired anytime, even in big corporate companies. It’s important for people in the music industry to understand and set their terms of work with those they are working with. That way, even if you get fired or ditched, you can at least console yourself knowing you were being paid while you worked.

I like being straightforward. Many people have been disappointed in the industry because, when they were working with artists, they did so from a place of assumption rather than clarity, and sometimes from a place of pretence. You have to set clear expectations when working with artists to avoid being disappointed by them.

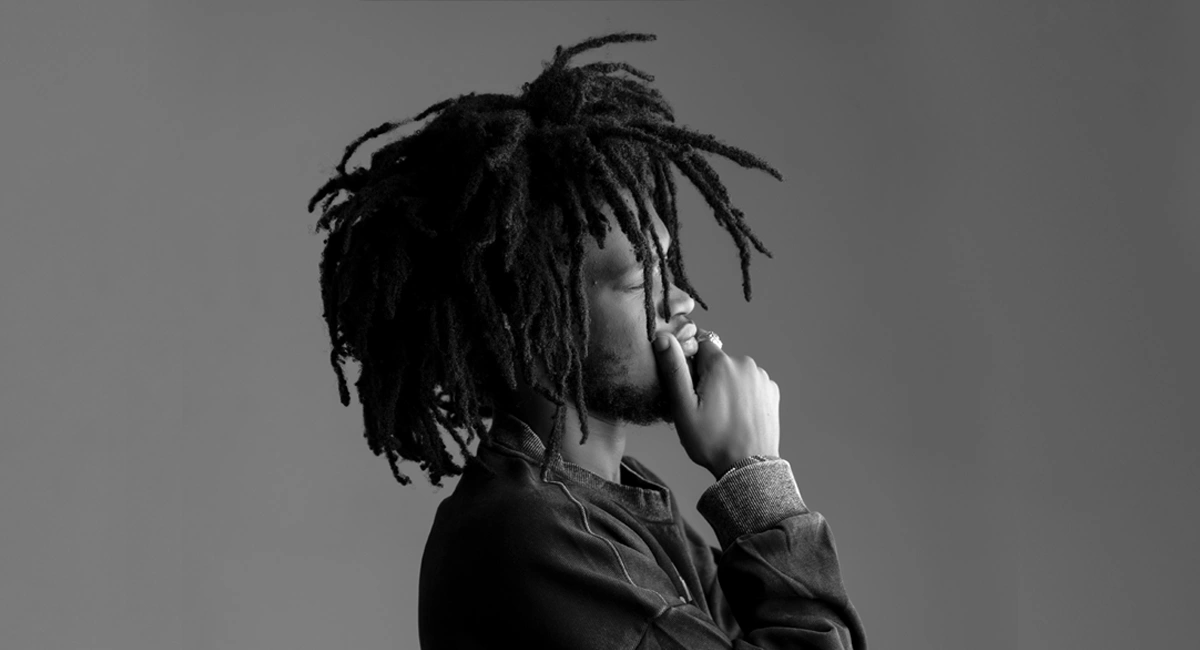

If you felt even a bit of his hustle in this story, give the music a listen—your play counts! Jenesis Kimera is out there proving it track by track. You can also follow him on Instagram, X, and subscribe to his YouTube.

This interview [Part One and Two] with Jenesis Kimera was conducted on 28 July 2025 by Isaac Odwako O. and transcribed into text by Joshua Mwesigwa for Nymy Net.